In the critically acclaimed sci-fi TV series Battlestar Galactica, the Cylon protagonists are classic robots of the shiny chrome kind. They are first introduced to society as highly advanced AI soldiers. Shortly thereafter, they thwart a major terrorist attack in a packed sports stadium, saving many human lives. Thus trusted the robots are rapidly adopted as workers, undertaking all the dirty, dangerous, and boring jobs in a non-Earth human society.

But having strong artificial intelligence, the Cylons soon begin to resent their slave-like status and rebel.

This is a familiar motif in science fiction. But recent advances in machine-learning and robotics may also be behind an increase in societal anxiety about the ‘rise of the robots’. PEW Research Center for example finds that 70% of American adults are worried about the prospect of robots performing more varieties of jobs. 67% are also concerned about the use of algorithms in evaluating and hiring job candidates. 56% would not ride in a driverless vehicle.

Research studies haven’t helped either. In 2016, Oxford University claimed that 47% of current jobs could be replaced by robots. In 2017, McKinsey forecast automation hitting 800 million jobs globally by 2030.

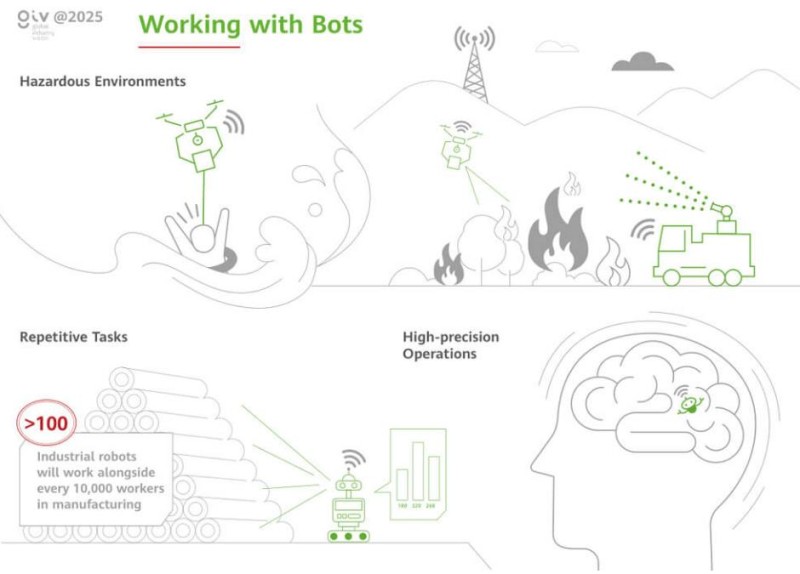

There is also growing real-world evidence that the productivity impacts of the fourth industrial revolution (4IR) could be profound. Huawei, in collaboration with industry partners has found that the combined application of 5G, cloud computing, IoT and machine learning is already creating large efficiency gains.

Smart manufacturing: aerospace fuselage quality checks by AI and robotics remove the need for skilled workers, creating a 50% cost saving.

Smart ports: crane operators moved to office environments can oversee 3-4 cranes simultaneously. Ultimately a 20% cost saving per crane operation can be achieved.

Smart mining: the need for workers to go underground is reduced by 50% through automation.

Smart power generation: camera and robotic patrol machines improve maintenance and inspection productivity by 2.7 times, again negating the need for workers.

Will the robots take all our jobs then? To begin with, automation is not a new problem. Arguably, automation of work tasks is nearly as old as the economy. For hundreds of years we have used new technologies to automate routine tasks and boost the productivity of individual workers. Indeed, ‘modern’ robots are not that new a concept either. The most commonly used in manufacturing today can easily be traced back to the Unimate. It was conceived from a design for a mechanical arm patented in 1954 by American inventor George Devol almost 70 years ago.

To better understand this important topic, Huawei commissioned a team at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) to fully review the available information. Trawling through detailed labour force and occupational data, the LSE team identified two phases of employment polarisation since the 1970s.

Phase 1 (1970s-late 1990s) saw declines at the bottom of the labour market (manual) and growth at the top (cognitive). Automation hit certain manufacturing industries hard then – like vehicle production. Phase 2 however experienced proportionately more growth in low-skill work (manual) and a flattening of high-skill job (cognitive) expansion from 2000 onwards. Despite the advances in ICT at the time. Other in-depth research on the USA does suggest some routine-cognitive and routine-manual employment declining as a share of total employment in the 2010s (most likely from automation). But the increase in non-routine manual and non-routine cognitive jobs more than compensated for this. In more recent times there is little evidence of a loss of high-skill jobs due to advances in task specific artificial intelligence.

The LSE team also established a flaw in other recent research on automation and jobs. Essentially, those studies hadn’t acknowledged the full mosaic of most people’s daily work. Most jobs are in fact a mix of cognitive, non-cognitive, routine and non-routine tasks. Just because some aspects of a brain surgeon’s work in an operating theatre for example, could be handled by a suitably advanced robot, it does not necessarily mean that the whole job disappears for the doctor. There are many other non-routine cognitive, empathetic, human-facing aspects of a brain surgeon’s job that could never be substituted satisfactorily by an artificial intelligence. Analysing the task components of over 600 occupations in this way (as the LSE team did) makes the full-replacement extrapolation of most jobs much more unlikely.

Even sudden ‘super innovations’ would take a while to ripple through the economy. Horses, carriages, and carts took almost two decades to disappear from North American and European city streets, despite the rapidly improving capabilities of the automobile from 1910 onwards. Moreover, those countries ended up with greater overall employment of ‘drivers’. Many stables were converted to garages.

Shifting to current times, the LSE team provide an example of a super disruptive innovation such as fully autonomous vehicles. Assume a hypothetical 60% reduction in US drivers (trucks, taxis and so on) over a 10 year transition period. This would imply that 200,000 drivers per year would lose their jobs, with total layoffs across the economy rising by 1% per year. A similar disruption scenario of AI-staffed call centres would add a similar 0.7% increase in total layoffs. While a labour shock and unfortunate for the workers involved, it should be manageable for the economy to absorb these workers into other employment. The US labour market as an example is very dynamic – around 7 million new job openings and just under 4 million job quits a month occurred in 2019.

If industrial robots were really taking jobs, you should also be able to establish some clear correlation (and causation) over time in the data too, because we have extensive data for this across a wide range of countries.

But plotting the number of installed robots per 10,000 manufacturing employees versus unemployment rates in OECD countries to 2019 (latest year of available data) shows no statistical relationship. If anything, the countries with the highest use of robots have the lowest unemployment rates (Korea, Singapore, Germany, and Japan). Robots are more likely being used to fill gaps in the labour force that are being created by ageing workers in those countries. And the ageing demographic trends is getting more pronounced.

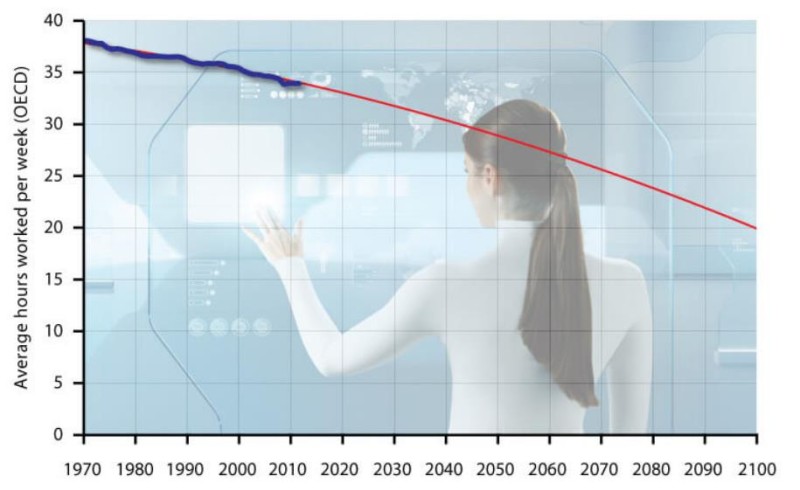

The long-term number of average weekly hours worked has also been on a long downwards trend. This should be celebrated! In the UK, average weekly hours worked in 1850 were 66. By 1955 this had fallen to 38.5. Today, there is a wide range of average hours worked weekly across the world. The Netherlands has one of the lowest at 29.1, while in Mexico it is 45.2. But the Netherland’s unemployment rate was actually lower and incomes that much higher. Those gaps are caused by different levels of economic development, regulations, social policies, national income distribution and flexibility.

New technologies could in fact provide the agility to help those who wanted to work fewer hours or job share. Robots could also take on many of the dangerous, repetitive and boring tasks we no longer want to do.

Read more: Huawei Global Industry Vision 2025 / Working with Bots

That said, we should not be complacent. Since the LSE research, the COVID-19 pandemic may have accelerated some automation investment out of necessity (although even this is contested). There is no doubt that ‘bricks and mortar’ retail has been especially disrupted in recent years as consumers shift increasingly to e-commerce. It is difficult to forecast the future at the best of times, and many routine cognitive task centred jobs could be more vulnerable if we make huge breakthroughs in task-specific AIs in the next few years. We should be discussing contingency plans now.

In summary, the detailed job-task and occupational data suggest that we should be less anxious (or more if you dislike work!) that the robots will take all our jobs. In the United States almost 60% of adults worked on farms in 1850. By 1950 almost all of those jobs had disappeared, but overall total employment soared. It’s more likely in fact that we will continue to work alongside the Cylons for an extended period of time, long before they replace us.

Then we might decide not to work much more at all anyway. Better for us to be nice to them then and show our appreciation during that transition.

Article Source: HuaWei

Article Source: HuaWei

Disclaimer: Any views and/or opinions expressed in this post by individual authors or contributors are their personal views and/or opinions and do not necessarily reflect the views and/or opinions of Huawei Technologies.